Real estate has traditionally been an excellent investment for individual and professional investors alike. When made a part of a well diversified portfolio that includes stocks, bonds and other traditional and alternative investment classes, real estate can enhance the portfolio’s returns while helping to diversify volatility and risk. In recent years a number of real estate investment products have been developed to enable investors to participate in owning quality, professionally managed properties. This Guide explains the several types of real estate investment funds available in the U.S. and the factors that investors should consider when evaluating an investment.

Real estate has traditionally been an excellent investment for individual and professional investors alike. When made a part of a well diversified portfolio that includes stocks, bonds and other traditional and alternative investment classes, real estate can enhance the portfolio’s returns while helping to diversify volatility and risk. In recent years a number of real estate investment products have been developed to enable investors to participate in owning quality, professionally managed properties. This Guide explains the several types of real estate investment funds available in the U.S. and the factors that investors should consider when evaluating an investment.

1. Introduction to Real Estate Investments

To understand the nature of real estate investment funds, it will be useful first to contrast the traditional way to invest in real estate: the direct investment.

Direct Real Estate Investments

The simplest way to invest in real estate is to purchase an income-producing property, such as an apartment building, office building or shopping center. While many people have made successful direct real estate investments over the years, the non-professional investor faces a number of obstacles to achieving investment success by purchasing properties on his own:

The High Cost of Individual Properties. In most parts of the country, even the smallest of income-producing properties will require an investment of at least $25,000. However, an investment in just one (or a few) properties involves risk because the success of the investment will depend on the successful operation of that one particular property. It is now universally accepted that for any type of investment it is always possible to reduce this type of investment risk by investing in a diversified portfolio of investments. For real estate, this translates to at least ten (and preferably 20 or 30) decent sized properties, which would require investment capital of several hundred thousand dollars at a minimum. If the investor wished to diversify further by separating his or her money into different investment classes (e.g., residential, commercial, industrial, retail and international) and different geographic areas, substantially more investment capital would be required. And of course a truly diversified investment portfolio requires investments in other asset classes, including stocks, bonds and cash.

Let us say that a hypothetical investor decides to put 20 percent of his or her investment capital into a portfolio of ten properties. Let us also assume that the investor is able to find ten small apartment buildings or retail stores that cost an average of $100,000 each and that a bank will loan 80 percent of the purchase price. This means that the investor must put up $200,000 ($20,000 per property), and therefore must have total investment capital of $1 million. All but the most wealthy individuals simply can not afford to invest at this level. And even if they could, should they really be investing in the cheapest, smallest properties that they can find? After all, in most parts of the country $100,000 doesn’t buy much. Wouldn’t it be better if they could invest in large, well located, stable office buildings, shopping centers, apartment complexes and other high quality property types?

Skill and Effort Required for Purchase. Successful real estate investing requires experience, skill and lots of time. Some of the skills required for a successful purchase of an investment property include: researching to find the best geographic markets for investment; choosing the right property class (e.g. shopping center vs. office building); finding the right brokers in the locality; sifting through hundreds of potential properties; writing and negotiating offers; finding the most competitive mortgage lenders and negotiating the best financing deals with them; dealing with escrows and closings; and retaining accountants and attorneys to properly structure the investment.

Not surprisingly, most non-professional real estate investors tend to buy only in the market where they live. However, their local market may not be a particularly good one for investment compared to other parts of the country. And even if it is, they are still incurring undue risk compared to a portfolio of properties diversified throughout the country.

Property and Investment Management. Once the investment has been made, it must be managed and monitored. Rents must be collected, vacant units advertised and re-leased and rental rates monitored for possible adjustment to keep up with the market. The property must be kept in good repair, and the services of gardeners, janitors, pool cleaners, elevator service technicians and the like retained and supervised. The financial side of the operation, including bookkeeping and tax accounting, will add additional time and expense. If a tenant doesn’t pay its rent and must be evicted, or if a tenant files for bankruptcy, the investor will have to retain attorneys. Many of these functions can be contracted out to local property management firms, accountants and the like, albeit at a price. However, the investor must still keep a close eye on his or her investment and must interact with the advisors, which also takes skill and time.

Lack of Liquidity; High Transaction Costs. It is often said that more money is made on properly exiting an investment than in entering it at a favorable price. The real estate market is subject to fluctuations in response to changes in economic conditions, such as interest rates and employment levels. The successful real estate investor needs to monitor market conditions and be prepared either to sell when markets begin to change or to ride out the downturn. Real estate markets are also illiquid. Transaction times are measured in weeks and months, unlike the stock market, where a sale takes place in seconds.

Limited Investment Opportunities. The individual investor is pretty much limited to purchasing properties that are already leased up and paying a steady rental stream. While these can provide attractive returns to the experienced investor who is willing to put in some time to manage and monitor the property, full time real estate professional have opportunities for investments offering far greater potential for return. Examples include real estate development, where new houses or buildings are constructed and then sold or rented out, and turnaround opportunities, where a property is remodeled and then sold or rented out at a profit.

Real Estate Investment Vehicles

To solve these problems, a wide variety of pooled real estate investment vehicles have been devised, including REITs, private real estate funds, syndicated real estate partnerships, group trusts, insurance company co-mingled real estate funds, real estate mutual funds, and REMICs, CMOs and other types mortgage pools. All of these involve the pooling of a number of individual properties, mortgages or other real estate-related investments into a diversified, professionally managed investment vehicle owned by multiple investors. The analogy is to the mutual fund, which allows individual investors to buy, for a relatively low cost, a portion of a diversified, professionally managed portfolio of stocks or other securities. Public and private real estate funds (including REITs) are among the best types of vehicles for individuals and smaller institutions, and are the focus of this Guide.

2. Types of Real Estate Investment Funds

Real investment funds can be categorized in several different ways:

Public and Private Funds

Public funds are those whose stock trades in the public securities market. To invest you place an order through your stock broker just as you would for corporate stocks. Most public real estate funds are organized as real estate investment trusts (REITs). REITs are like mutual funds, except that they invest in real estate or mortgages instead of stocks and bonds. Like corporations, they have their own management and board of directors. But, unlike corporations and like mutual funds, they are not separately taxed as long as the pay out substantially all of their income as dividends to their investors.

REITs, however, are not open-ended like most mutual funds–they do not issue and redeem their own shares based on the daily net asset value of their portfolio. Instead, their stock trades on a stock exchange or Nasdaq, just like a corporate stock. Like mutual funds and public corporations, REITs are subject to a slew of laws and regulations requiring public disclosure of information as well as restrictions on the manner in which they conduct business.

Private real estate funds are those that do not trade in the public securities markets. They usually take the form of limited partnerships (LPs) or limited liability companies (LLCs). The LP partnership interests or LLC membership interests are sold to a small group of investors, and the capital that is raised is then used to make real estate investments. These investment (equity) interests are either sold directly by the sponsor of the fund or though a securities broker. The sponsor manages the fund as the general partner of the LP or the managing member of the LLC. Because of the requirements of federal and state securities laws, the investment interests may only be sold to a relatively small group of sophisticated investors that meet suitability requirements concerning their business and investment experience and minimum income and net worth. Private funds are treated as partnerships for tax purposes, meaning that they are not separately taxed—a proportionate share of their income, deductions, capital gains and other tax items is passed through to each investor, who then includes them on his or her personal tax return.

The partnership structure is very flexible. For example, unlike a REIT, a private fund need not distribute its income to its investors, but can reinvest it in additional properties, offering investors the opportunity to compound returns. The flexibility of the private fund also allows for sophisticated tax and estate planning opportunities for investors that are not possible with a publicly traded security such as a REIT stock. Unlike REITs, however, private funds are relatively illiquid, since there is no regular market for their equity interests. For this reason, they have a limited investment term (usually 5 to 10 years) at the end of which their assets are sold and they are dissolved with the profits being distributed to the investors and the manager.

Finally it should be mentioned that a REIT does not have to be publicly traded, and there does exist a small market for private REITs that serve a specialized market. For instance, some foreign investors derive benefits in their local jurisdictions by investing in the U.S. through private REITs.

Pools and Property Specific Funds

Real estate investment vehicles come in pooled and property-specific forms. Public REITs are almost always pools, and many private funds are as well. In a pool the fund manager has the discretion to buy and sell properties as long as they fall within the fund’s investment criteria. Thus, the skill of the manager in selecting, managing and “harvesting” (i.e., selling at the right time) investments is the key consideration when deciding whether to invest in a particular fund.

In contrast, property-specific vehicles are almost always private. They are formed to invest in one or more specific properties, which are identified and discussed in detail in the offering documents for the fund. They are not usually considered true “funds,” as that term generally implies that the investment capital will be invested in multiple investments selected by the fund manager. They represent a mid-point between the pool and the direct investment in real estate. Like the direct investment, the investor has the comfort of knowing exactly in which properties he or she is investing and has a chance to analyze their financial profile and other characteristics before committing to the investment. He or she can even go and visit the properties before committing to the investment. Like a pool, the property-specific fund includes professional management of the investment, so that it is truly passive. But because the investment is tied to specific properties, these funds to not have the ability to alter their portfolios as market and other factors change over time. This can be an advantage or a disadvantage depending on the skill and fortunes of the manager.

Equity, Mortgage and Hybrid Funds

Real estate funds, both public and private, can be classified as equity, mortgage and hybrid funds. An equity fund owns equity in real estate, either directly or through partnerships or joint ventures with others. A mortgage fund, as its name implies, makes or purchases mortgages on real estate. Mortgage funds are almost always pools. A hybrid fund invests both in real estate mortgages and equity.

Mortgages are generally safer than equity investments in real estate, but have lower investment returns. There are a number of other efficient ways to invest in mortgages, from direct purchases of individual mortgages to investments in mortgage securities such as Ginnie Maes and collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs). For this reason, most real estate funds are equity funds. According to the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT), less than 2 percent of public REITs are mortgage REITs and less than 3 percent are hybrids; the other 95 percent are equity REITs. While the statistics for private funds are harder to come by, the ratios are probably similar. For this reason, the remainder of this Guide focuses solely on equity funds.

Industry-Specific Funds

Public and private real estate funds can also be categorized by industry sector. The following is a breakdown of REITs by sector, as published by NAREIT:

- Retail 20.1%

- Residential 21.0%

- Industrial/Office 33.1%

- Specialty 2.3%

- Health Care 3.8%

- Self Storage 3.6%

- Diversified 8.5%

- Mortgage Backed 1.5%

- Lodging/Resort 6.1%

Private funds, both pooled and property-specific, are also available in a wide variety of industry specializations.

Geographically Concentrated Funds

Public and private funds are available that only invest in particular geographic regions, such as Southern California or New England. International real estate funds are available that focus on specific countries, such as Japan, enabling investors to take advantage of differing market conditions in other parts of the world. Frequently, the fund manager will retain a local company to act as the fund’s representative in the foreign country.

Investment Strategies

As will be discussed below in greater detail, a fund’s investment strategy cuts across all of these classifications. A fund’s investment strategy refers to the types of returns targeted (e.g. current income vs. capital appreciation), the levels of investment returns targeted, the amount of investment risk that the fund will tolerate, and the strategy that the fund manager intends to use to attain those targets. Fund strategies can be placed on a continuum ranging from “core” investments in prime properties enjoying dominant positions in major markets, to “value-added” investments in properties where development, re-leasing, renovation and other similar techniques may be applied to increase the market value of the properties, to “opportunistic” strategies that seek to exploit major market inefficiencies or periods where the capital markets are closed to real estate transactions. This continuum can be seen as a sliding scale of increasing risk with correspondingly higher targeted investment returns.

Funds of Funds; Real Estate Mutual Funds

Funds of funds are simply investment funds that invest in a diversified portfolio of other investment funds. While more usual with venture capital and other types of private equity funds, there are now a number of real estate funds of funds in the market. Because they charge their own management and other fees and expenses on top of those charged by the funds in which they invest, it would seem that the investor could always do better by investing directly in the portfolio funds.

However, funds of funds can still be an attractive choice for two reasons. First, private real estate investment funds usually have fairly high investment requirements, and a minimum investment in each portfolio fund might be more than the investor can afford or wishes to invest. Second, the fund of funds manager provides valuable services to its investors by analyzing and choosing which particular funds will go into the portfolio, monitoring and altering the fund of funds’ portfolio over the life of the investment, and providing reporting and other administrative services.

While their legal structure is different, real estate mutual funds are analogous to funds of funds for the public fund arena. A real estate mutual fund is simply a mutual fund that invests in REIT stocks and, sometimes, stocks of other publicly traded real estate companies. Again, the same considerations–smaller required minimum investment amounts and professional portfolio management–have established a market for real estate mutual funds.

3. The Long-Term Advantages of Incorporating Real Estate in Investment Portfolios

There are number of reasons for investors to include real estate (either direct investments or funds) in a diversified investment portfolio:

Stability

Studies have shown that real estate values are more stable than stock prices, which have consistently higher volatility.

Strong Current Yields

Real estate investments typically return regular cash distributions to the investor at rates that have, on average, historically exceeded those from bonds, CDs and other fixed-income investments.

High Overall Returns

Real estate investments generally provide two types of return: current cash distributions and capital appreciation. According to numerous academic and professional studies, the total return on real estate investments and real estate funds has historically fallen between those for bonds and those for stocks. Risk, measured by volatility of returns, is generally closer to bonds than stocks.

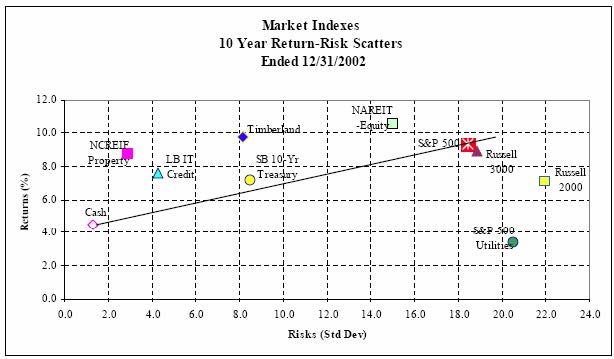

A good example is provided in the following chart, which was prepared by the University of California’s Committee on Investments in March 2003 as part of a major revision to its investment guidelines and asset allocation policies for real estate investments in the University’s endowment. It shows the average 10-year returns from 1992 -2002 for several asset classes. Two real estate indexes are represented: the NCREIF Property Index, an index of “core” institutional real estate holdings, and the NAREIT equity index, an index of publicly traded REIT stocks.[1] The line in the chart connects the data points for cash, 10-year treasury bonds, and stocks, and represents the risk/reward profile of portfolios consisting of various proportions of those three basic asset classes. Note that both real estate data points have superior risk/return profiles, as indicated by their positions above the line.

Source: University of California, Office of the Treasurer

Source: University of California, Office of the Treasurer

Portfolio Diversification

Diversifying an investment portfolio over different classes of assets is crucial for obtaining maximum returns while minimizing risk. Many studies in recent years have confirmed that real estate investments have low risk correlation with equities, making them an ideal way to reduce portfolio risk while maintaining or enhancing overall returns. (This subject is discussed in greater detail later in this Guide.) Most large pension funds, university endowments, insurance companies and other conservative institutional investors hold 5 to 10 percent of their assets in real estate equity, and financial advisors to high net-worth individual investors often recommend an even higher real estate allocation.

Inflation Hedge

Unlike bonds, CDs and other fixed-income investments, both cash distributions and capital appreciation on real estate investments tend to increase to keep pace with inflation. Cash distributions are protected because many leases are subject to annual rent escalations and are structured to pass along increases in operating costs to the tenant. In addition, rental levels generally rise with inflation and in a properly maintained building rents can be continually increased to market as leases are renewed or new leases signed. This factor both protects current income against inflation and ensures that the value of the property appreciates with the overall real estate market.

Tax Benefits

Private real estate funds organized as LPs or LLCs can often provide tax benefits to their investors. Both types of organization are treated as partnerships for tax purposes, with a proportionate part of the fund’s income, loss, gains, tax credits and other tax attributes passed through to the investors. These appear on the annual Schedule K-1 that the fund sends to each investor, showing where to include his or her share of these tax items on his or her tax return. In a typical private fund that owns income-producing property, the benefits that an investor can realize include the following

- The investor’s share of the fund’s taxable income will be reduced by a proportionate share of the fund’s depreciation deductions, typically by 25 to 35%.

- The investor’s share of the fund’s taxable income will be reduced by a proportionate share of the fund’s deductions for operating expenses and for interest paid on its mortgage loans.

- When the fund’s property is sold, the gain is typically taxed at the lower capital gains rates.

These benefits will be offset by some phantom income–that is, income that arises because a cash expense by the fund is not allowed as a tax deduction. (This is discussed in detail below.) Examples include payments that must be capitalized and depreciated over a number of years (such as the purchase of a new roof with a ten year life) and the portions of debt service payments that constitute a repayment of principle. However, in most cases the depreciation deduction, which does not reduce cash flow, will outweigh these phantom income amounts, and the investment will shelter from income taxation a significant portion of the fund’s operating income. In a typical leveraged real estate investment, the effective tax rate on the cash flow generated by the investment is frequently less than 10 percent. In contrast, interest received on a CD or bond (other than a low yielding municipal bond) is fully taxable as ordinary income.

Both real estate and partnership taxation are complicated subjects, and investors need to consult with their accountants and advisors before committing to a real estate investment in the LP or LCC form. Advance planning can prevent unpleasant surprises from the alternative minimum tax, the passive loss rules and other tax provisions that can affect real estate investments.

4. Advantages of Real Estate Investment Funds over Direct Investments

For the foregoing reasons, real estate investments should be included in almost every diversified investment portfolio. As will be discussed later in this Guide, the addition of real estate investments can be expected to increase overall returns while reducing portfolio risk.

Having decided to include some real estate in their investment program, most individual investors, as well as many institutional investors, will find that funds offer them a number of advantages over direct investments, and are thus the preferred way to invest. These advantages include:

Ability to Diversify Real Estate Holdings

Because in a fund a number of investors join together to combine their investment capital, they can collectively purchase a greater number of properties than they could afford to purchase as separate investors. This ability to diversify is a primary attraction of funds, especially for investors with limited investment capital. Investors can also spread their investment capital across several funds with different industry and geographic concentrations to achieve further diversification.

Access to Higher Quality Properties

The pooling of investment capital also enables the fund to purchase larger, better quality properties than those the investors could afford to purchase on their own. Through a REIT or private fund, even the most modest investor can own an interest in some of the largest, most prestigious properties in the country.

Access to Value-Added and Opportunistic Strategies

Value-added and opportunistic real estate investments have the potential to provide greater investment returns than passive investments in core properties. However, if the investor is not a real estate professional, he or she will not have the expertise to engage in these strategies. While many professional real estate investment advisors will accept individual clients, they typically require a minimum investment of $1,000,000 or more to open a segregated managed account. The private fund offers these investors a good alternative, especially for those who wish to allocate a smaller amount of their portfolio to aggressive strategies.

Professional Management

A fund offers full time professional management of its portfolio investments, creating a truly passive investment. At the property level, the fund manager’s staff works with brokers, vendors, tenants, property management companies, accountants and others to completely manage the operation of the portfolio properties on behalf of the investors.

Liquidity

REIT stocks that trade in the public securities market are as liquid as any other publicly traded stock. Private fund interests are much less liquid, although they can be traded on a private basis through brokers or firms that specialize in matching buyers and sellers in the secondary markets. In this regard, they are probably no less liquid than a direct investment in a property. Funds also have limited lives, generally 5 to 10 years, and are self-liquidating in the last years of their life.

5. Fund Investment Strategies

As discussed earlier, in addition to classifying real estate equity investment funds by their industry and geographic focus, their investment strategies must be considered. Investment strategies can be distinguished by their (1) investment objectives, (2) targeted rates of return, and (3) maximum level of risk. These three considerations are all interrelated: strategies that emphasize steady cash distributions over capital appreciation typically have lower risk, while strategies that emphasize the potential for large gains through capital appreciation are usually more risky.

Investment strategies are generally broken down into three categories:

- Core Strategies. These involve investments in prime properties enjoying dominant positions in major markets. The investor can expect the properties to be fully occupied and leased up at current market rents, and exposure to lease expirations not to be great. A core strategy has the investment objective of providing a steady current income, modest capital appreciation and relatively low risk. Risk can be further lowered by lowering the amount of leverage in the fund’s portfolio.

- Value-added Strategies. These involve investments in properties that are not performing at their full potential and where the game plan is to bring to bear the talent and experience of the fund manager to increase the properties’ value and investment returns. Examples of value-added strategies include: development of vacant land; renovation of older properties, leading to an increase in rental rates; and re-positioning strategies, where the mix of tenants in buildings is upgraded and rents increased (often preceded by a building renovation). These strategies involve more risk than core strategies because of the uncertainty of the success of the value-adding projects, and thus value-added funds strive for higher returns than core funds.

- Opportunistic Strategies. An opportunity fund seeks to exploit major market inefficiencies or periods where the capital markets are unavailable to the real estate owners. The real estate markets experience periods where property values are abnormally high or low compared to historical averages and opportunity funds seek to exploit mispricings during these times.

Often, changes in government policies can provide investment opportunities. In the past 20 years we have seen two major changes that depressed real estate prices for several years each: the Tax Reform Act in 1986, which eliminated many tax incentives for real estate investment, and the savings and loan crisis of the early 1990s, which led to the Resolution Trust Company dumping an extraordinary number of properties on a real estate market that could not absorb them all. Both events provided excellent opportunities for opportunistic buyers and resulted in substantial profits when the markets eventually recovered.

Opportunity funds also make mortgages and equity investments at times when banks are not lending or the capital markets are closed to real estate owners, usually charging hefty rates and fees in the process. An example occurred in 1998, when financial crises in Asia and Russia led to devaluations of foreign currencies, and U.S. banks sharply curtailed their lending to all types of borrowers–even those, like real estate owners, with no foreign exchange exposure. Another example was the technology bubble of the late 1990s, when “smart” equity investors were only interested in Internet stocks, and even owners of top quality real estate had a difficult time raising capital.

REITs tend to concentrate on core and, less frequently, value-added strategies. This is partly because of the legal requirement that REITs invest in operating assets and distribute substantially all of their income to their shareholders, which make it difficult for them to engage in value-added strategies. For instance, REITs generally can not develop properties unless they intend to hold and operate them as part of their portfolio, as opposed to selling them off when completed. And because REITs are publicly traded and open to investors of every sort, they tend to shy away from high-risk strategies such as opportunistic investing.

Private real estate funds are free to take a more active role, and because they are only open to institutions and individuals who are sophisticated and have a high net worth, they are able to implement more aggressive strategies. For example, private real estate development funds are often formed to purchase vacant land for development or existing buildings for renovation; either as property-specific partnerships or as pools. Unlike REITs, these private funds are free to sell the developed properties once they have been completed and leased out, because the investment returns from development are usually higher than those from operating completed properties.

6. Choosing the Right Real Estate Investment Funds

Having established that real estate investment funds are a superior way for most investors to invest in real estate, the question becomes how to choose which funds to actually invest in. If the future could be foreseen, then picking the best real estate investment funds would be easy: we would take the ones that will produce the highest overall return. Of course, the performance of a given investment can not be foretold with accuracy. (As Will Rogers once said, “Buy stocks that go up. And if they don’t go up, don’t buy them.”) In any investment there is always an element of risk that the expected return from the investment will not be achieved. The goal of any investment choice thus becomes achieving the highest return for a given level of acceptable risk.

Asset Allocation and Modern Portfolio Theory

Modern portfolio theory is the study of constructing portfolios of assets (investments) that maximize returns for a given level of risk. It is a complicated subject beyond the scope of this Guide. Many investment professionals use some version of portfolio theory in setting up and maintaining investment portfolios for their clients. Often they use sophisticated computer programs to assist them in the process. To summarize the technique in general, the portfolio is first allocated across broad asset classes (for example: 60% stocks, 15% bonds, 15% real estate and 10% cash). These allocations are generally made on the basis of the historical returns and risk (volatility) of each asset class, projections based on economic indicators of the expected future performance of each asset class, and how closely the risk for each class is correlated to the risks of the other classes. The asset allocations are updated from time to time as changes in the economy and markets dictate; this is known as “rebalancing.” Once the allocations to asset classes have been made, a minimum number of discrete investments must be made in each asset class to provide statistical diversification.

Returns and risks of the various asset classes are usually based on historical returns of broad indexes, such as the Wilshire 5000 for stocks, and the volatility of those returns, which can be quantified as a percentage, known as the standard deviation. For non-public asset classes, such as private real estate funds, this data may not be widely available and the advisor may have to rely on averages and surveys of past returns from similar funds.

Allocating Investments to Real Estate Investment Funds

A few general comments can be made as to the application of all of this to real estate fund investing. First, most large institutional investors, who have access to the most sophisticated professional advisors and analysts, have some real estate in their investment portfolios, typically in the range of 5 to 10 percent of total investment assets. Allocations to real estate have risen in recent years, mainly due to historically low yields on bonds.

Second, most asset allocation models use the NCREIF or NAREIT indexes to represent real estate as an asset class. The NCREIF index represents institutional direct real estate investments (and is frequently used a proxy for private real estate funds). The NAREIT index is an index of the prices of REIT stocks. These indexes have been closely correlated over the years, but are not identical, and several recently published studies have demonstrated that a 50/50 mix of the indexes provides a better risk/return profile than either index by itself. The implication is that an equal mix of REIT stocks and private real estate funds is preferable to just one or the other.

Third, once they have set their overall allocation for real estate, most major institutions pick their individual investments based on relatively subjective factors, including their past relationships with fund managers and the performance history of managers with whom they have not invested before. Investing in a particular fund comes down to (1) evaluating the investment to see that it falls within the investor’s goals for targeted returns and risk, (2) evaluating the manager’s ability, reputation and past performance, (3) making sure that the investment strategy, industry and geographic concentrations, and other factors fit in with the investor’s other real estate investments and does not cause any undesired concentrations in the investor’s portfolio, and (4) reviewing the structure of the investment to make sure that it is acceptable to the investor. These principals may be followed by individual investors as well.

The fund manager may provide projections of the fund’s anticipated performance and risk, based on the manager’s experience in the past with similar properties and expectations for market conditions over the life of the fund. This is generally more feasible for property-specific funds, where detailed projections of income, expenses and debt service can often be made with reasonable accuracy and total returns then projected under a number of different scenarios for future inflation, rental rates, etc. For a pool fund, this is not practical, and the fund manager will rarely provide projections. The most that may be available is the manager’s past performance with similar funds, although these may not be relevant because of differing market conditions. Another important consideration is the expected timing of distributions over the life of the fund.

What kind of Returns can Investors Expect?

What levels of returns can investors expect from real estate investment funds? The following is the opinion of the author. At the low end of the risk and reward spectrum are the core funds. Using the NCREIF index of total returns as a starting point, annual pre-tax IRRs[2] of 6 to 10 percent should be targeted. Total returns on REIT stocks and core private funds should fall in the same range on a long-term basis. At the other end of the spectrum are the opportunity funds, which

generally target pre-tax IRRs of 20 percent or more. In the middle are the value-added funds, which generally target pre-tax IRRs of 12 to 18 percent. Of course, as with any other investment class, there is no guaranty that any of these targets can be achieved, and real estate like every other asset class will experience periods of investment losses.

A Closer Look at the Numbers

A little bit of knowledge of how the financial aspects of real estate investments are analyzed by professionals can greatly assist the investor in choosing the best real estate investment funds to include in his or her portfolio. (A related post contains a more detailed discussion of these concepts.) For any real estate equity investment (whether a direct investment or through a fund), the investment’s potential to make money for the investor can be broken down into five relatively independent elements. By assessing an investment’s potential for generating each of these five types of profits and returns, the investor can make a surprisingly good overall assessment of the investment without having to crunch a lot of numbers.

The Initial Cash-on Cash Return. The initial cash-on-cash return is simply the amount of cash expected to be received by the investor in the first year of the investment as a percentage of his or her investment. For a REIT that has been paying an annual 6% dividend, the cash-on-cash return is obviously 6%. For a new private fund, which will not have a past operating history, the investor will have to dig through the fund offering documents, examine the manager’s track record and consult market statistics[3] to estimate what types of cash-on-cash return can be expected.

The initial cash-on-cash return is most important for core investments, where it will constitute the largest element of the investment’s expected return. If this is the investor’s goal, then the analysis should focus on the prospects for stability of the investment’s dividends/cash distributions, such as the quality of the properties and tenants, whether there are long-term leases in place, and the strength of rentals in the local real estate markets and industry sectors where the fund will be investing.[4] On the contrary, if the investor is seeking a more aggressive investment, then the cash-on-cash return will be a lesser consideration–the bulk of the investment’s overall return will instead come from capital appreciation. In strategies such as real estate development, there may be no current return at all—all of the profits come from selling off the developed properties.

Appreciation in Operating Income. Unlike a bond, which pays a fixed coupon for the life of the investment, a real estate investment’s cash-on-cash return will change over time as the cash flow generated by the properties changes. On average, cash returns from any investment in income-producing properties (whether directly or through a fund) can be expected to increase each year at or above the rate of inflation. This is because as a general matter rental income net of operating costs (known in the business as “net operating income” or “NOI”) tends to rise with inflation, while mortgage payments are usually fixed, so that the net cash flow generated from the investment should on average rise every year even after adjusting for inflation. Of course, this is true only in the long run, and there will be years where rents, and thus cash returns, will remain flat or fall. Operating income appreciation not only benefits investors through increases in their net cash flow from the investment, but by increasing the underlying value of the property, which will be realized by the investors when the property is sold.

This potential for appreciation in net operating income is a key to analyzing a value-added real estate investment. If the fund manager can successfully increase a property’s net operating income, say through a re-leasing program to increase rents to market rates or by reorganizing the property’s management to reduce operating costs, then the corresponding increase in net operating income will directly translate into increased cash payouts to investors and higher property values when the properties are eventually sold. Therefore, a primary goal of any value-added strategy should be to generate net operating income increases above the rate of inflation.

Market Appreciation. A second type of appreciation is market appreciation, which is caused by an overall rise in real estate prices in the local market in which a property is located. In a rising market, a property’s value will rise even if there is no corresponding increase in its net operating income. Of course, the opposite can happen in a falling market.

Market appreciation is a component of the overall return of core real estate strategies, where it provides an element of capital appreciation to the investor. However, it is usually not as important as initial cash-on-cash return and operating income appreciation; in the typical core investment, perhaps at most 20 percent of the overall return can be expected to come from market appreciation, which can not be realized until a property is sold or refinanced.

Taking advantage of potential market appreciation is the basis of most opportunistic investment strategies. An opportunity fund attempts to buy properties at favorable prices, either at the bottom of market cycles or during periods where prices are depressed because of market conditions, such as a credit crunch. They are basically just using the oldest investment strategy of all: buy low, sell high.

The amount of money invested in opportunity funds exploded in the mid-to-late 1990’s, when real estate markets began a long climb out of the lows seen in the early part of the decade. Despite the “hot” real estate markets of the past few years, many opportunity funds continue to raise new investment capital. The careful investor must ask him- or herself whether current market conditions are right for investing in opportunistic strategies, and, if not, whether the fund in question has modified its strategy for today’s markets. Care must especially be taken when examining past results of the opportunity fund or its manager, because they may represent gains made by investing at the bottom of the market, conditions that are very different from those of today.

Mortgage Principal Paydown. The cash distributions to real estate fund investors, such as REIT dividends and regular distributions from private funds are derived from the operating income of the fund’s properties after payment of operating expenses and mortgage debt service. Most fund mortgages are similar to a home mortgage, in that part of the debt service payment is applied to reduce the principal on the mortgage. When the fund sells the property, it only has to repay the outstanding balance of the mortgage; the remainder has already been paid from the property’s net operating income prior to the distribution of any cash to the investor. The amount previously repaid in effect comes back to the investor as an additional element of capital appreciation.

Mortgage principal paydown is an aspect of almost every any fund strategy, because real estate investments are almost always leveraged. Thus in comparing different real estate investments it is probably not as important as the first three elements discussed above. However, if a mortgage was placed on a property in times of high interest rates, or if the mortgage has been in place for a number of years, there may be opportunities for the fund to refinance at a lower rate or for a higher principal amount. The former would lead to an increase in dividends or operating cash distributions to the investors, while the latter would allow the difference between the new mortgage amount and the principal on the old mortgage to be distributed to the investors or reinvested in new properties. In some property-specific funds, the returns projected to investors may assume a refinancing in the future, in which case the investor should determine what his or her return will be if the hoped-for refinancing does not take place.

Tax Benefits. As already discussed, real estate investments, unlike most bonds, CDs and other fixed income investments, often provide significant tax benefits. It is therefore necessary to compare both pre-tax and after-tax returns when comparing different investments. As there are all sorts of factors that affect the ability of a given inventor to utilize the benefits of a particular investment, the investor’s accountant or other tax professional should be consulted before making any investment that involves significant tax consequences.

The Importance of Evaluating the Fund’s Management

In this era of accounting scandals and corporate malfeasance, it is important for investors to examine the management of any company in which they plan to invest, whether it is a real estate investment fund or not. Jones Lang Lasalle, a leading global provider of integrated real estate and investment management services, has recently issued a report in which they identify eight qualities that a real estate organization should possess. Their “eight great traits” fall into three phases of real estate services (planning, development and delivery), and while oriented more towards corporate real estate operations, they can be used as a blueprint for evaluating managers of real estate investment funds as well:

Planning:

- Relationship management: Understanding the business, anticipating and then translating business-unit issues into real estate solutions.

- Financial acumen: Protecting and enhancing the substantial financial assets and expenses associated with real estate.

- Process, rules and tools: Developing and maintaining well documented best-in-class processes.

Management:

- Owner of all occupancy costs: Understanding and taking responsibility for all aspects of real estate operations.

- Accurate data and metrics: Developing accurate numbers and communicating them throughout the organization.

- Allocation of occupancy costs: Allocating costs back to the business units in ways that promote desired behavior.

Delivery:

- Learning organization: Investing in, developing and motivating skilled employees.

- Infrastructure management: Partnering with other infrastructure functions—Finance, IT and Human Resources—to coordinate effective solutions.

Even the largest fund managers will delegate one or more of these functions to outside consultants, which can be a cost-effective way to obtain the necessary expertise without the overhead of a large staff.

7. The Risks of Investing in Real Estate Investment Funds

As with any investment, real estate investment funds have risks that must be understood and evaluated by the investor. These can be divided into market risks, property-specific risks, risks relating to the fund’s management and the structure of the fund, and regulatory and tax risks. Some of the more important risks are summarized below.

In general these risks should be discussed in detail in the offering documents prepared for prospective investors by the fund. This discussion should be read carefully and, if there are questions or concerns, discussed with the fund manager before investing.

Market Risks

Real Estate Markets. Real estate markets, like the markets for any other asset, go through cycles. Buying at the top of the market when price levels are significantly above their historical values is usually more risky than buying at the bottom of the market when prices are relatively low.

Interest Rates. Real estate is almost always leveraged (i.e., purchased in part with mortgage debt), and interest rate levels directly affect property values. Higher interest rates mean higher mortgage payments for the same loan amount, leading to more of the property’s net operating income being devoted to debt service. This leaves less free cash flow available to “cushion” the investment against a drop in rents when a tenant leaves, an unexpected increase in operating expenses occurs, an unexpected repair needs to be made, and the like.

Even though the interest rate on a mortgage is usually fixed for the term of the mortgage, changes in interest rates after a property is purchased can affect the real estate markets in general and thus the value of the property. This is most noticeable in the housing market. When interest rates rise, the monthly mortgage payment for a given loan amount will also rise, and thus the maximum price that a buyer can afford to pay for a house (and the maximum amount that the bank will agree to lend) will be reduced. Conversely, when rates are low, monthly mortgage payments will be lower, and buyers can afford to take out bigger mortgages and buy more expensive houses, pushing prices up.

The Economy. Changes in the economy, such as changes in job growth, recessions, and other general economic conditions all affect buyers and renters of real estate of all kinds, which in turn influence prices in the real estate markets.

Property-Specific Risks

Concentration and Similar Risks. Most funds will have investment criteria that concentrate their investments in a specified industry or specified geographical location or have a relatively narrow investment strategy. This necessarily leads to a lack of diversification and, possibly, will concentrate the fund’s portfolio in a small number of discrete investments. It is important for investors to understand these factors in the context of the allocations of their overall portfolio, and if necessary to diversify through different investments that are not highly correlated with the fund investment under consideration.

Local Market Conditions. Changes in the local economy can affect properties located there, such as the closing of a large plant or the influx of new immigrants.

Local Regulatory Changes. Cities and other local governments have many powers that can dramatically affect real estate values. For instance, if a city imposes a moratorium on new construction, values of existing properties will generally rise.

Demographic Changes. Local markets change their demographics over time, as people and businesses move in and out of the locality. These demographic changes can substantially alter real estate values over time.

Tenant Risks. Properties that are leased to tenants always involve risks that tenants will default or go bankrupt or will not renew their leases. This is a greater risk when the property has only a single or a few large tenants than if it has many small ones.

Obsolescence. As time goes by, properties need to be maintained and improved so that they do not become obsolete and unable to compete with newer properties. Examples range from technological obsolescence (for example, not having high-speed Internet access) to the property’s physical appearance.

Leverage. While leverage generally allows real estate investors to buy more properties and to increase returns on their investments, it also adds the risk that in an economic downturn or other situation where the property’s income falls off, there may not be enough income to service the mortgage. In this case, a foreclosure of the mortgage may occur, which would wipe out the investment.

In addition, even an equity fund can end up as a mortgage holder if it sells a property and provides financing to the buyer. In this case the fund and its investors will have the risk that the buyer may default on its note, requiring the fund to foreclose on the property or making the fund a creditor in the buyer’s bankruptcy.

Liquidity. Real estate is relatively illiquid, with the time to complete a purchase or sale measured in weeks or months. If economic or other conditions suddenly change, the fund may not have time to liquidate its investments before they loose a substantial part of their value. This will directly affect the investors’ returns.

Tax and Regulatory Risks. Changes in property tax rates, the imposition of new taxes and fees, and the adoption of new regulations (such as environmental, noise and traffic regulations) can all affect the economics of owning real estate.

Risks of Value-added Funds. Value-added funds will have additional risks associated with their particular investment strategies and their managers’ skill and ability to implement them. For instance, a development fund will have all the risks inherent in real estate construction, such as labor problems, supply shortages and inspection and other regulatory delays.

Fund Management and Structure Risks

Skill and Experience of the Fund Manager. The skill and experience of the fund’s manager is obviously critical to the fund’s overall performance. In the case of development funds and other value-added funds, the skill of the developer and any significant outside parties and consultants is also important. Their track records on past funds and other real estate investments are important facts to consider.

Lack of Investor Control. Investors in private funds organized as LLCs and LPs have very few voting and other control rights over the fund’s operations. Investors in funds organized in some states, such as California, do have some minimal statutory voting and other rights. Other states, including Delaware and Nevada (both popular with fund managers) offer virtually no protection to members and limited partners in LLCs and LPs. The fund documents must be analyzed to ensure that the fund investors have certain minimal rights, such as the right to remove the manager for fraud, embezzlement or other serious infractions.

As with other public companies, REITs are subject to SEC and stock exchange regulations that require levels of stockholder voting and other rights that are considerably stronger than under state law.

Conflicts of Interest and Excessive Fees. A private fund manager may be subject to a number of conflicts of interest and potential conflicts of interest. For instance, if it manages more than one fund with overlapping investment criteria, then it should have neutral procedures for allocating investment opportunities among the funds. Often the fund has business dealings with the manager or an affiliated company or person that can give rise to a conflict of interest. These must be carefully understood and analyzed. It is important to note whether independent appraisals, studies or reports have been obtained to justify the fairness of the transaction that gives rise to the potential conflict.

A related issue is the level of fees payable to the fund manager and its affiliates. The fund offering documents should have a detailed discussion of all such fees. The cumulative effect of many different fees can make a reasonable investment return to the investors all but impossible to achieve.

Similar considerations often apply to a REIT’s management, especially when management owns a large percentage of the REIT’s shares. While in principle the fund’s board of directors should provide independent oversight of management to guard the interests of shareholders, as in other public corporations REIT boards are not always up to the task.

Examples of common conflict situations include the following:

- The fund is buying properties from the fund manager or an affiliate. It is critical that an independent appraisal support the purchase price and terms to ensure that the fund is not overpaying for the property.

- The fund manager or an affiliate is taking a brokerage fee or an “acquisition fee” from sellers of properties to the fund. Brokerage fees are usually paid by the seller, not the buyer, and are split between the seller’s and the buyer’s brokers. However, if the fund bought the property directly it presumably could have negotiated with the seller for a reduction in the purchase price equal to the amount that would have been paid to the buyer’s broker. It could be argued that the manager’s duties (for which it already is being paid) should include representing the fund on property acquisitions, especially in a property-specific deal where there are no brokerage services left to perform. Nevertheless, brokerage and acquisition fees are very common in private funds; in fact, historically syndicators of property-specific deals took most of their compensation up front as a large acquisition fee. At a minimum, any brokerage fees on acquisitions should not exceed the commission rates charged by unaffiliated brokers in the same market.

- Brokerage fees on property sales paid to the manager or an affiliate are not as big a concern since they would have to be paid to an unaffiliated broker in any case. The manager should represent in the fund offering documents that the commission will not exceed the market rate.

- It is not uncommon for the manager or an affiliate to be the property manager for the fund’s properties. This is usually acceptable if no more than a market-rate fee is charged.

- The fund manager typically sets its annual management fee and the amount of its carried interest (i.e., interest in the fund’s net profits) and presents them as a fait accompli to potential investors in the fund offering documents. They are generally not negotiable by the individual investor. Investors should consult with their advisors to make sure that these fees are not unusually high. Most private real estate investment funds charge annual management fees of 1 to 3% and have carried interests between 15 and 25 percent.

Liquidity. In addition to the fund’s liquidity risk on its portfolio properties, a real estate investment fund investor may face liquidity risk on his or her fund investment. This is not an issue for a public REIT, since its shares will trade in the public securities markets. For a private fund, however, there will be no trading market and a private sale will have to be arranged through a broker. Such sales can take considerable time to arrange and the seller may have to take a substantial discount on the sales price to consummate the transaction. Also, because of regulatory requirements, the consent of the fund manager and considerable paperwork (including legal opinions) will generally be required.

Lack of Government Review of Private Funds. The prospectus for an offering of stock to the public by a REIT is subject to detailed review by the SEC and the REIT is subject to a number of continuing reporting, proxy solicitation, merger and other regulations by the SEC, stock exchanges and state regulators. In contrast, private funds are not subject to any of these, and the offering documents must therefore be scrutinized by investors and their advisors before they make the investment.

Phantom Income, Passive Activity and other Tax Risks. As discussed above, a private fund is taxed as a partnership, and its income, gains and other tax items are allocated annually among the partners. These items are allocated regardless of whether the fund makes a corresponding cash distribution. If in a given tax year the fund investors are allocated taxable income greater than the amount of cash distributed to them, they still have to pay tax on this “phantom income.” Phantom income usually arises when fund cash expenditures are not deductible for tax purposes. Examples include payments for a new roof, which must be capitalized and depreciated over the life of the roof; payments for the fund’s syndication expenses, which must be capitalized and may not be amortized, and the portions of the fund’s debt service payments that constitute repayment of principal, which are not deductible. In cases like these the amount of phantom income probably will not be too large compared to the amount of non-phantom income, and the corresponding cash distribution from the fund would normally be more than sufficient to pay the taxes on both the phantom and non-phantom income allocated to the investor. In contrast, when a fund is permitted to sell a property and reinvest all of the proceeds in a new property, the investors will be allocated all of the taxable gain and will receive no cash from the fund to pay the taxes.[5] In cases like these, investors should make sure that the fund is required to make an annual partial cash distribution that at a minimum covers the taxes on the income and gains allocated to the investors for the corresponding year.

8. Real Estate Investment Fund Structures Explained

REITs

Most REITs are corporations, and investors become stockholders, just like in other corporations. And like corporations, they have their own management and are subject to the overall authority of their boards of directors. The main differences arise out of the restrictions placed on REIT activities by the tax laws in return for pass-through treatment. These have already been discussed above.

Private Funds

Unlike REITs, private funds always have a pre-set structure for distributions of cash and other key financial terms. Over time these terms have become well established in the market. The following is a brief summary.

Manager’s Investment. Often, but not always, the fund manager will invest capital into the fund. The amount invested is generally 1% for large funds and a somewhat higher percentage for small funds.

Distribution Waterfalls; Preferred Returns; Hurdles and Clawbacks. The “waterfall” is the section of the fund’s partnership or operating agreement that governs cash distributions. It usually applies to “distributable cash,” which is the cash left over after all fund expenses and liabilities have been paid and an operating reserve established. Two types of distributable cash are usually distinguished: (1) “cash from operations,” which is the cash received from rents and other property income, less payment of all operating expenses and debt service on mortgages; and (2) “cash from capital events,” consisting of (a) the net proceeds from sales of fund properties after payment of all transaction costs and repayment of any mortgages secured by the sold property, and (b) net refinancing proceeds, which are the net cash proceeds from refinancing a fund property’s mortgage for a higher amount (commonly known as a cash-out refi). In a pool fund, the investors’ capital contributions to the fund must be allocated to each of the fund’s investments so that capital event distributions are properly allocated.

Cash from capital events is generally split between the investors and the fund manager as follows:

- First, in some funds the investors are be entitled to a “preferred return.” This is a return, generally 6 to 12% per annum, paid on their actual investment in the fund. The preferred return is only paid on unreturned capital, so if the investors previously received a return of some of their initial investment from a previous capital event, they will no longer earn the preferred return on the amounts repaid. The manager also gets a preferred return on its contributed capital.

- Second, 100 percent of the remainder is paid to the investors and the manager in proportion to their capital contributions until they have received the percentage of their capital that was allocated to the property that is being sold or refinanced

- Third, the remaining cash, which represents the profit on the capital event, is split among the investor group and the manager; the manager’s portion is called its “carried interest.” There are a number of different formulas for this. Often, there is straight percentage split, most commonly 80% to the investors and 20% to the manager. Another variation is to have the split percentage change when a specified amount, called the “hurdle amount,” has been received by the investors or when they have exceeded a return based on a specified IRR or other measurement, called a “hurdle rate.” For instance, the investors may get 80% of the cash until they have achieved a 20% IRR, and then the split reduces to 50/50. Another common variation is the manager “catch up” – the Manager first gets allocated 80% of the profits until it has received, say, 20% of the cumulative profits distributed (including the preferred return previously distributed); all remaining profits are then split 80%/20%. If the fund generates sufficient cash, this type of formula will in effect reverse the economic effect of the preferred returns previously paid out to the investors and put the fund on a straight 80/20 split of all cash above the capital initially contributed by the investors and the manager.

In most funds, each time a property is sold, the hurdle rate is recalculated with respect to all properties liquidated since the inception of the fund. This means that if a property when sold does not provide sufficient profits to achieve the hurdle rate (or is sold at a loss), profits on future property sales must be great enough to cover the deficit as well as the hurdle rate for the subsequent sales before the manager qualifies for the more favorable profit splitting ratio (50/50 in our first example). The reverse situation can also arise: early property sales may generate large profits, resulting in distributions to the manager at the 50/50 stage, while later property sales may be at a small profit or a loss, pushing the investors’ cumulative return below their hurdle rate (or below the sum of 100 percent of their capital contributions plus the preferred return in funds using the preferred return structure). In some funds, if this situation persists at the end of the fund’s term, the fund is entitled to “claw back” funds from the manager, up to the total distributed at the 50/50 stage, until the hurdle rate is again achieved. (In a fund with a preferred return and a manager catch-up, the claw back applies to funds distributed at the catch-up stage.) The claw back sometimes collateralized by assets pledged to the fund by the manager or is guaranteed by the manager’s principals.

Cash from operations is usually distributed in the same way as cash from sales and refinancings, except that because there has been no capital event involving fund property, step 2 is skipped.

Capital Reinvestments. Funds that are pools are often permitted to reinvest a portion of the cash otherwise distributable from a capital event into new properties. In this case investors should make sure that the fund is required to make enough of a cash distribution to cover the tax on the phantom income that will be allocated to them from property sales.

Management Fee. The fund manager usually receives an annual management fee of 1 to 3% of the fund’s capital in addition to its carried interest. Sometimes, the management fee is based on the net asset value of the fund’s properties, based on their most recent appraisals.

Investment Term and Dissolution. The term of the typical private real estate investment fund is 5 to 10 years. If the fund is permitted to reinvest profits, this ability usually terminates 2 to 3 years before the fund’s term expires. Often the fund manager has the right to extend the term of the fund for one or two years if market conditions at the expiration of the term are not favorable for liquidating the fund’s properties.

Nature of Investors’ Interests; Limited Liability. Investors in LPs are always limited partners, and like members of LLCs or stockholders of a corporation, have limited liability. This means that their liability is limited to their investment in the LP or LLC plus, in some circumstances, amounts previously distributed to them. If the LP or LCC has a large judgment against it or files for bankruptcy, its partners and members will not be personally liable for any additional amounts.

Management and Control: Voting; Removal and Replacement of Fund Manager. A discussed under “Conflicts of Interest” above, investors in LPs and LLCs have very limited voting rights, control rights or rights to remove or replace the manager. However, an amendment to the fund’s partnership or operating agreement will require in most circumstances the approval of at least a majority in interest of the investors, making it important to carefully review the terms of this document.

Manager’s Powers and Discretion. The powers of the LP or LLC are generally limited to those necessary to buy, operate, finance and sell properties and other related activities, and the manager generally can not deviate from these without approval of the investors. This is unlike the case with corporations, which generally can engage in any lawful activity without limit.

9. Conclusion

A diversified investment portfolio should include real estate investments to increase returns and lower risk; allocations of up to 10 percent for institutions and 10 percent to 20 percent for individuals are typical. Real estate funds offer an excellent means of investing in a professionally managed diversified group of properties, and offer a number of advantages to the investor who does not want or have the experience to personally manage properties. Real estate investment funds take the form of publicly traded REITs and privately offered LPs and LLCs. Recent studies suggest that investors should split their real estate investment allocation among both classes. Funds are available in a wide variety of industry and geographic focuses. While REITs are generally limited to conservative core investment strategies, more aggressive value-added and opportunistic strategies are widely available in the private fund sector. For inventors who are seeking greater investment returns and whose portfolios can tolerate some increased risk, these types of private real estate investment funds will be attractive. In addition, private funds often can provide significant tax benefits to investors.

[1] It should be noted that the Committee stated that the NCREIF data point probably understates the actual risk of the institutional real estate investments that it represents because private real estate holdings are revalued only when they are reappraised (generally once a year), which tends to produce smaller variations than a stock or REIT index that is revalued every day.

[2] See this post for a discussion of the internal rate of return (IRR) as the best measure of the overall return of a real estate (or any other kind of) investment.

[4] Information on conditions and prospects for the major real estate markets in the U.S. can be found in a number of places, such as the excellent series of quarterly surveys published by Marcus & Millichap.

[5] Techniques such as 1031 exchanges may be used to defer income taxes on the gains in these situations.